Now that we’ve covered Microphones and Power Mixers/Amplifiers (see Quarter Note June and September 2010 issues, respectively), it’s time to talk about the last of the main elements in our PA system: speakers.

In a sense, speakers are microphones in reverse. While microphones take sounds and turn them into electronic signals, speakers take electronic signals and turn them into sounds. Conversion of sound between acoustical sound waves and electrical signals is very difficult to do accurately. Thus, as with microphones, every speaker will sound a bit different from every other.

Speakers make sound by physically pushing out and pulling in against the air. As a general rule, you need larger speakers to create lower frequency sound waves and smaller speakers to create higher frequency sound waves. Thus, speaker cabinets for PA systems and home stereos always have at least two different kinds of speakers (technically called “drivers”) inside them. Lower frequencies are covered by woofers, and higher frequencies are covered by tweeters.

The electrical signal that comes out of the Power Mixer contains both high and low frequencies. It is the job of the “crossover,” an element built into the loudspeaker cabinet, to split the signal and send it to the appropriate driver. Some speakers come with a Crossover Control knob, which allows you to change the frequency at which the signal is split. This can be very handy if you use your PA for many different types of vocal/instrumental set-ups.

Perhaps one of the most important things to understand about speakers is their coverage and throw. All speakers have a coverage pattern, expressed in degrees, which tells you the horizontal and vertical spread the speakers will cover. In addition, all speakers have a maximum throw, the distance they will remain effective.

To complicate matters a bit, we must understand that high frequency sounds are far more directional than low frequency sounds. As a visual analogy, think of loudspeaker cabinet as a pair of lights: one of the lights is a bare bulb (the woofer) and one is a narrowly focused flashlight (the tweeter). If you turn on a bare bulb in a room, the light will be fairly evenly distributed. If you turn on the flashlight, the beam of light will be narrowly focused in the direction it’s pointed.

In practical terms, this means that people sitting to the side or rear of your speaker cabinets won’t be getting their share of high frequency sounds, but they will still hear low tones clearly. The overall sound, then, will be more muffled to them. The best-designed speakers minimize this difference in coverage as much as possible. Still, even the most expensive cabinets are much more directional at high frequencies than at low ones. Thus, understanding how to place your speakers is key to making sure everyone in the audience gets good sound.

Speaker placement requires consideration of several factors – how ‘live’ (reverberant, echo-y) the room is, how large the audience is, avoiding feedback – too many to cover here. But let’s take a moment to see how a speaker’s coverage pattern factors into your speaker set-up decisions.

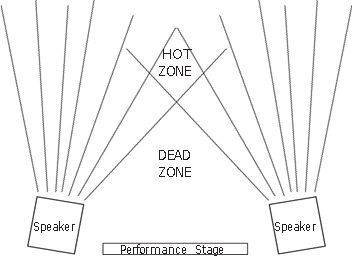

Let’s say your speakers have a horizontal coverage of 60 degrees each, and you place them as pictured here. As you can see, the coverage area of both speakers combine to create a “hot zone” and a “dead zone.” Audience members in the “hot zone” may find the sound too loud, while those in the “dead zone” may have trouble hearing, or they may get enough volume directly from the performers where they don’t need as much sound from the speakers anyway.

It’s important, when setting up your speakers, that you (and/or your sound person) move around the room while someone is playing or singing through your system, to make sure the sound coverage is as even as possible

and sounds they way you want it to. Make sure you sit in the chairs and not just listen from a standing position. You want to hear the sound the way the audience will hear it, so you can make adjustments accordingly.

In more ‘live’ (reverberant, echo-y) rooms, amplification can create huge sound problems, because sound bounces back and forth, muddying the result terribly. The more musicians playing, the muddier the sound will be. If you’re playing in a very ‘live’ room, using as little amplification as you can get away with is often the best move.

Possible hot zone, dead zone, and poor sound quality solutions include: raising speakers a bit higher to give everyone in the room more of a wash of sound; adjusting the angle of the speakers on the stands; moving speakers closer together and aiming them outward (rare); adding additional speakers(s); and EQ-ing and/or adjusting levels of individual voices and instruments. Every situation is different. The most important thing to do is to listen.

We didn’t get to cables and PA set-up basics this time around, as promised in the last issue. We’ll cover that in the March 2011 Quarter Note, with the fourth and final installment of this series.

−Hilary Ann Feldman