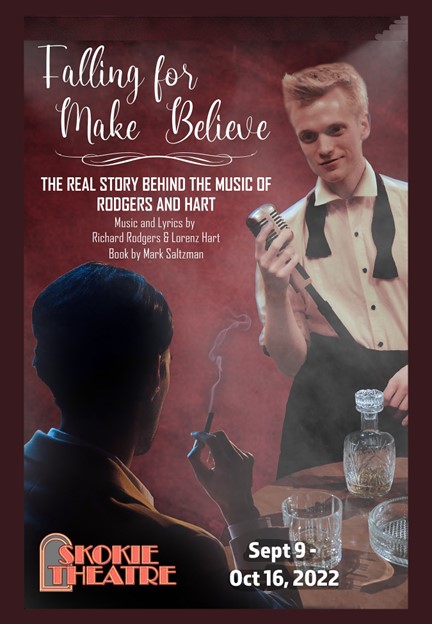

September marks a significant event for Chicago area fans of The Great American Songbook. The Skokie Theatre will be staging the Mid-west premiere of Mark Saltzman’s new musical, Falling for Make Believe, about the monumental 25-year Broadway collaboration, from 1918 to 1943, of composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Lorenz “Larry” Hart. Since Falling for Make Believe primarily focuses on Hart, and the chaotic life he led when not writing lyrics, let’s review his world, and the clues to it in his writing, in anticipation of Saltzman’s musical play.

Hart was introduced to Rodgers when he was 23 and Rodgers only 16. They grew up only a few blocks from each other north of Central Park, each as one of two sons in an upper middle class Jewish family. But though their backgrounds make them sound quite similar, in real life they couldn’t have been more different.

Rodgers was businesslike, well organized, and quite handsome as a young man; Hart was a disheveled misfit who was very sensitive about his physical appearance. At slightly under five-feet tall, with a disproportionately large head for his miniature body, he saw himself as an undesirable freak.

And then there was his sexual orientation—unlike his contemporary, Cole Porter, he was ashamed that he was gay. He certainly didn’t try to slip subtle homosexual references into his lyrics as Porter occasionally did—he was very secretive about his proclivities and would have been horror-stricken if his beloved mother had learned the truth.

What he did insert into his lyrics, time and time again, was his personal unhappiness, his desperate feelings of being lonely and unlovable.

During the course of a Rodgers & Hart musical, there was often a situation when the heroine (sometimes the hero) found herself bereft, usually because she was in love with someone who didn’t love her (at least not at the moment!). Rodgers, who always wrote the music first, would write an appropriately sad tune for Hart to set, and Hart, presumably writing for the character, would respond by providing a unintentional window into his tortured soul. Examples of these lyrics abound in Hart’s body of work. Let’s look at them chronologically.

His first example, for their first Broadway book show in 1925, Dearest Enemy, seemed innocent enough. “Here in my arms, it’s adorable,” he wrote, setting Rodgers’ distinctive four note phrase with a four-syllable word. But then he followed up: “It’s deplorable that you were never there.” In his comments on this early lyric, the inveterate rhymester played up the quadra syllabic rhyme but ignored the sentiment it expressed.

His next such notable lyric, from Peggy Ann, was far more revealing. At a time when Hart, with his tricky rhymes, was doing battle with the prevalent, insipid “June/moon” culture in popular songs, he was also rebelling against the era’s numerous Pollyanna numbers. “Where’s that rainbow you hear about?/Where’s that lining they cheer about?” he wrote. “It is easy to see all right/Ev’rything’s gonna be all right—/Be just dandy for ev’rybody but me.”

But why would everything be all right for everybody else but Hart? In Betsy, a show that opened, literally, the night after Peggy Ann did, he had the heroine expound upon the reasons for her misery: “This funny world/Makes fun of the things that you strive for./This funny world/Can laugh at the dreams you’re alive for./ If you’re beaten conceal it!/There’s no pity for you./For the world cannot feel it./Just keep to yourself./Weep to yourself.”

The shows opened at the end of Rodgers & Hart’s first full year of success, 1926, which had included SIX shows, including one in London, and a tour of Europe. After more than seven difficult years, they had finally leaped to the top of their profession, but early career achievements clearly did not placate Hart’s inner demons.

The next year brought their biggest success of the decade, A Connecticut Yankee, and Hart managed to keep his personal pain out of his lyrics. But two years later, Hart was back with his most tormented lyric to date, identifying “the dreams you’re alive for” that he had alluded to in “This Funny World”:

“All alone, all at sea!/Why does nobody care for me?/When there’s no love to hold my love,/Why is my heart so frail,/Like a ship without a sail?”

Soon afterward, Rodgers & Hart were off to Hollywood, where they toiled unhappily for four years as Broadway dried up in the early days of the Great Depression. Because the movie studios dictated the projects, Rodgers & Hart had little control over their work, and Hart was not able to add to his catalog of woe. But as soon as they returned to Broadway in 1935, Hart resumed, adding a new title to his sad profile with almost every new show.

For their first show back, Jumbo, in 1935, Hart contributed this lyric: “No use, old girl,/You might as well surrender./Your hope is getting slender./Why won’t somebody send a tender/Blue Boy, To cheer a/Little Girl Blue?”

But for their next show, On Your Toes, Hart hinted that a “Blue Boy” had already appeared. How ever, this Blue Boy provided no cheer, because he didn’t reciprocate the love of Little Girl Blue: “Fools rush in, so here I am,/Very glad to be unhappy./I can’t win, but here I am,/More than glad to be unhappy./Unrequited love’s a bore/And I’ve got it pretty bad./But for someone you adore,/It’s a pleasure to be sad.”

So Hart was now trying to acclimate himself to his sad fate by framing his loveless condition as pleasurable. Since it has been reported that his sexual preferences may have been masochistic, perhaps he was now trying to align his emotional state with his physical cravings.

His next autobiographically revealing lyric was surely his most famous. In Rodgers & Hart’s following show, Babes in Arms, he seemed to cast himself as the object of a wish fulfillment fantasy, with the singer being his imagined lover: “My funny Valentine,/Sweet comic Valentine,/You make me smile with my heart./Your looks are laughable,/Unphotographable,/Yet you’re my fav’rite work of art./Is your figure less than Greek?/Is your mouth a little weak?/When you open it to speak/Are you smart?/But don’t change a hair for me,/Not if you care for me,/Stay, little Valentine, stay!/Each day is Valentine’s Day.”

Alas, Hart was not able to sustain either of these mindsets, pleasurable sadness or wish fulfillment. Two shows later, in I Married an Angel, he was back to the loveless self-pity he had depicted nearly a decade earlier in “A Ship Without a Sail”: “Spring is here!/Why doesn’t the breeze delight me?/Stars appear!/Why doesn’t the night invite me?/Maybe it’s because/Nobody loves me./Spring is here, I hear!”

He followed that up by another, circling back to the 1920s, in the next Rodgers & Hart show, The Boys From Syracuse, revisiting the disillusioned view of life he portrayed in “This Funny World”: “Falling in love with love/Is falling for make believe./Falling in love with love/Is playing the fool./ Caring too much is such/A juvenile fancy./Learning to trust is just/For children in school.”

The Boys From Syracuse, in 1938, was a high point in the Rodgers & Hart collaboration and evoked some of Hart’s best work. He was motivated by at last being able to use his beloved younger brother Teddy in one of his shows, casting him in a starring role. But after that, his chaotic life started to disintegrate more and more rapidly, pulling Rodgers’ work down with him, and that was reflected in the mediocre scores they produced for their next two shows. It took an out-of-the-blue suggestion from novelist John O’Hara to resuscitate Rodgers & Hart and result in their most audacious, and revivable, show, Pal Joey, in 1940.

But after that, the final act of this long-term partnership played out. For the first year since their initial success in 1925, there was no new musical or movie score from Rodgers & Hart in 1941. The next year brought Rodgers & Hart’s last new show, By Jupiter, and Larry’s most autobiographical lyric yet. For the first time, he inserted his evocative last name into the title of one of his sad ballads: “Nobody’s Heart” was almost screaming to have the “e” removed and reveal itself as “Nobody’s Hart.” Here’s the full lyric:

“Nobody’s heart belongs to me,/Heigh ho, who cares?/Nobody writes his songs to me/No one be longs to me—/That’s the least of my cares./I may be sad at times,/And disinclined to play,/But it’s not bad at times,/To go your own sweet way./Nobody’s arms belong to me,/No arms feel strong to me./I admire the moon/As a moon,/Just a moon./Nobody’s heart belongs to me today.”

After By Jupiter, Hart dissolved the collaboration when Rodgers insisted on musicalizing the rural folk play, Green Grow the Lilacs, as their next project. It was a terrible fit for the urban and cynical Hart, and it seems evident that Rodgers was using this subject matter to force a change of partners to the bucolic Oscar Hammerstein 2nd, whom this material suited perfectly. Oklahoma! became the greatest hit in musical theatre history up till then, and after it opened, the guilty Rodgers reached out to his former partner with one last chance. He suggested writing a half dozen new songs for a revival of their biggest 1920s hit, A Connecticut Yankee, the project Hart had wanted to work on instead of Green Grow the Lilacs.

It was in one of these six songs that Hart laid bare his most revealing lyric of all.

After they had met way back in 1918, the friend who introduced them, Philip Leavitt, wrote: “It was all so simple. Dick sat down at the piano, and Larry said, ‘What have you written?’ and Dick played some of his music, and it was really love at first sight.”

Little did Leavitt realize the full meaning of that statement. “Can’t You Do a Friend a Favor?” was one of the last lyrics Hart ever wrote before he died of pneumonia on November 22, 1943. He contracted his final illness after the opening night of A Connecticut Yankee, when he was lying drunk in a gutter during an all-night rainstorm. The song’s first chorus went:

“Can’t you do a friend a favor?/Can’t you fall in love with me?/Life alone can lose its flavor,/You could make it sweet, you see!/I’m the dish you ought to savor,/Something warm and something new;/I could do my friend a favor,/I could fall in love with you.”

In the second chorus, the reality of his impossible, quarter of a century, unrequited attraction sank in, and Hart concluded his lyric, and his life, on a note of resignation.

“Can’t you do a friend a favor?/Let us part the way we meet./Life with you would have a flavor/ Sweet at times, yet bittersweet./I’m no dish you ought to savor./Feast your eye on something new./I will do my friend a favor:/I’ll be just a friend to you.”

But Richard Rodgers and Larry Hart were more than just friends. They were gifted collaborators, whose complementary skills with tunes and words fused together to create some of the most iconic songs in The Great American Songbook.

Show art courtesy of MadKap Productions.

MadKap Productions announces the Midwest premiere of the musical Falling for Make Believe by Mark Saltzman for 19 live performances at the Skokie Theatre, 7924 Lincoln Ave in Downtown Skokie. Sept 9 – Oct 16, Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm, with a Wed. afternoon matinee at 1:30 pm on Sept 21.

Starring Sean Michael Barrett as Lorenz Hart, and Sean Caron as Richard Rodgers. Also starring Donaldson Cardenas, Nate Hall, Cheryl Szucsits,, and Mandi Corrao as actress Vivienne Segal. The show is directed by Skokie Theatre’s Managing Director, Wayne Mell, with musical direction by Aaron Kaplan and choreography by Susan Pritzker. Lighting design is by Pat Henderson with costume design by Broadway World award-winner Patty Halajian. Wendy Kaplan produces for MadKap Productions

Tickets are $45 general admission, $38 for seniors and students and can be purchased online at SkokieTheatre.org or by calling 847-677-7761

by Charles Troy

1 comment

I’m happy to report Skokie Theater has a real winner with their biographical review Falling for Make Believe based on the lives and works of Dick Rodgers and Larry Hart.

Aficionados haven’t forgotten how great the Rodgers and Hart cannon is, having an indelible place in the American Songbook, but we like to forget the tragic ending of the collaboration, especially in light of Rodger’s historic success with his next collaborator, Oscar Hammerstein II.

Playwright Mark Saltzman sketches a scenario that tells the true tale (based on sound scholarship, in this writer’s opinion) which allows the story to be told in song. That is a delight since the score uses the writing team’s beloved hit songs. The main characters are all there: a stolid, business-minded Dick (played by Sean M.G. Caron) so self-possessed he can’t fathom what is eating his writing partner Larry. Also, their winning leading lady (a composite of Helen Ford and Vivien Segal, here called Vivian and played by Mandy Correo) who is insightful enough to understand the complex lyrics, but not wise enough to appreciate her wordsmith Larry’s hang ups.

The central menage is complicated by self-serving talent agent antagonist, Doc Bender, (played delightfully by Donaldson Cardenas) who exploits every friendship in show-business for his own ends, even discouraging Larry from bettering his life, lest it interfere with the parties and paychecks. The ensemble is complemented by thespian Cheryl Szucsists who cleverly plays several characters and sings the theme song the way a dreamy chanteuse fulfilling our desire to hear the classic music performed in top cabaret style would do it.

In this telling, Larry is a deeply sublimated gay in a homophobic world whose only joy is writing brilliant song lyrics full of wit and topical allusion, here played sympathetically by Sean Michael Barrett. Overcome by self-hatred, he is already on a downward spiral of addiction to alcohol when we meet him. Eventually Larry will propose a marriage of convenience with Vivian who doesn’t take him seriously, which otherwise could have been his last chance at a turnaround or maybe not.

The author cleverly depicts Larry’s real-life dilemma by introducing a fictional gay lover who can confront the issues of life in the closet and self-hatred objectively. But Larry can only see the life-line thrown his way as another exploitation. The well-rounded Fletcher Mecklen character is the audience’s way into the story as narrator and stand in (one suspects) for the story’s author. This roll is tastefully played by multi-talented Nate Hall. The production is graced with a beautifully well cast team of actor/singers.

The production team is excellent, led by director Wayne Mell with music direction by Aaron Kaplan and choreography by Susan Pritzker. The scene design, lighting and sound serve well. To this writer’s mind the star of the evening is the clever writing that allows us to ponder the depth of the songs and their complicated motivations with rich renditions.

Producer Wendy Kaplan has a long association with playwright Saltzman whose play Clutter was the inaugural production of Madcap Productions at the Greenhouse Theatre. She saw the original Falling for Make Believe in Los Angeles twelve years ago and has been waiting for the piece to be released for regional production after being held up by the estate of Mary Rodgers. One is thankful that the world is now more understanding about the poisonous consequences of self-denial. Thank you, Madcap, for this marvelous Midwest debut.

The production continues Friday, Saturday and Sundays through Oct. 16: SkokieTheatre.org – Don’t miss it!

By Daniel Johnson