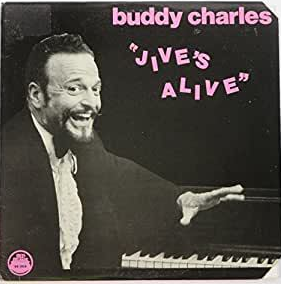

Behind the battered, upright piano at Chicago nightspot, the Acorn On Oak, there was a faux stained-glass window. And, if you were there at the right times, six nights a week, you would see a man with his head leaning back against the window, eyes shut, lean face framed by a devilish beard but offset by a beatific smile, music flowing out of his fingers, racing across the keyboard and into the hearts of his audience. That was Buddy Charles.

Behind the battered, upright piano at Chicago nightspot, the Acorn On Oak, there was a faux stained-glass window. And, if you were there at the right times, six nights a week, you would see a man with his head leaning back against the window, eyes shut, lean face framed by a devilish beard but offset by a beatific smile, music flowing out of his fingers, racing across the keyboard and into the hearts of his audience. That was Buddy Charles.

Born Charles Gries in 1927, Buddy came to music quite naturally. He said he used to sit under the piano and watch as his mother, Ruth, ran her fingers over the keyboard. His stepfather was jazz great, Mugsy Spanier. He started piano lessons in elementary school, but quit for a while once he joined the Mount Carmel boxing team and spent two years in the army. Then, when he returned to school, majoring in philosophy and psychology at Loyola University, he started to play again. On graduation he discovered there was a better market for talented entertainers than there was for teachers.

Buddy Charles was, quite simply, the best entertainer I ever saw. He wasn’t the best piano player, although he played brilliantly. He wasn’t the greatest singer, though he had a strong, upper baritone, lower tenor voice that was incredibly flexible. But when he blended his skills as a storyteller with his musical talents it was magical.

Buddy’s repertoire was incredible. Over the years I estimated the number of songs he could do from memory at between 15 and 20 thousand. And he not only could sing them, he could play them, tell you who wrote them and who performed them. In thirty-eight years of going to see him there was never a day when he didn’t play at least one song I had never heard before.

You didn’t go to see Buddy just to hear music. He put on a full show. And that was true whether the place was overflowing or there were just two or three people sitting round the piano bar. When he was asked to perform songs from a musical you’d find yourself in 1950’s New York or a little village in Russia. When asked to play the songs of a composer like Cole Porter or Richard Rodgers, he would play not only familiar works, but wonderful, lesser known tunes that you never heard before. And, as he would go along, he would tell you stories of why these songs were written. His iconic piece, Birth of the Boogie, was a journey across fifty years of American musical history in about forty minutes that left you feeling more knowledgeable and more joyful.

When he was asked to perform songs from a musical you’d find yourself in 1950’s New York or a little village in Russia. When asked to play the songs of a composer like Cole Porter or Richard Rodgers, he would play not only familiar works, but wonderful, lesser known tunes that you never heard before. And, as he would go along, he would tell you stories of why these songs were written. His iconic piece, Birth of the Boogie, was a journey across fifty years of American musical history in about forty minutes that left you feeling more knowledgeable and more joyful.

The Acorn became one of the “in” places for celebrities to visit. I was there when Liza Minnelli visited and when Oscar Peterson dropped in. At Buddy’s suggestion and with his accompaniment I once sang a duet with Lesley Gore. The casts of touring companies would come in and perform. I sat next to George Shearing at the piano bar several times (he always visited Buddy at least once when he was in town and often more than once). I sat next to Zelda Rubenstein (the little person from “Poltergeist”). I was also there when Allen Sherman sang a parody to the song from Doctor Doolittle. He sang, “If I could shtup with the animals,” using every euphemism for fornication that you can imagine and it had Buddy laughing so hard that he almost fell off the piano bench.

But, if you were a local musician, Monday nights was the night. With all the other clubs dark, the Acorn became a gathering spot for Chicago’s best. On any given Monday you would see Orlando Murden (composer of “For Once In My Life”), Dave Green, Audrey Morris, Joe Vito, Lucy Reed, Joyce Reeves, Nancy Barber, Frank Penning, Bobbi Jordan, Bill Acosta, Frank D’Rone, Lynn Woolgart, Bob Moreen, and Bruce Robbins. Also there’d be newcomers (at the time) like Denise Tomasello, Ester Hanna, Bob Solone, Joel Barry, Karen March, and Michael Laird. And you’d see local actors like Lee Pelty, Patty Wilkus and Ernie Lane. Impromptu singing groups would form for one night only and the night would pass rapidly into morning.

It wasn’t only musicians who frequented the place. Mike Royko (Mike listed Buddy as among the greatest musicians he had ever heard) was a regular there for years. Studs Terkel also would come in as did Rick Kogan, Howard Reich, Buck Walmsey and Bruce Vilanch. Harry Carey and Jack Brickhouse were there often. Ben Stein who owned the building would regularly come in with a beautiful girl or two on his arm. Local politicians and gangsters alike (actually not much of a difference) could be seen there. I was there one night when an obvious “wise guy,” sat down at the piano bar with a lovely blonde. When Buddy started a jazz tune she walked behind the piano and started to strip. Once she was undressed she started to rub up against him. Buddy scooted down the bench as far as he could, afraid her boyfriend would take umbrage and shoot him. When the song ended, she took a bow, put her clothes on and went back to her seat. Her fellow stood up with a big smile on his face, threw a hundred-dollar bill into Buddy’s tip jar and the two of them walked out.

What may be most amazing about Buddy and his career was that music and entertaining were nowhere near his top priority. Number one in his life was family. Although, it was thanks to music he met his wife. In 1950, Patricia Ferris was just finishing her tour of the show, “Mr. Roberts,” in San Francisco. Before she left for home she decided she wanted to hear some Dixieland jazz. Mugsy Spanier was in town so she went to see him and ended up spending hours talking to him and his wife, Ruth (Buddy’s mother). Pat had loved Chicago when the tour had played there, so she decided to stop and visit on her way home. Ruth invited her to stay at their house and the rest, as they say, is history. She met Buddy, they fell for each other and in 1954 they were married.

From that point on, Buddy, who had traveled all over the country playing, only looked for local work. Pat and he had four children, son Chris and daughters, Terri, Mandy and Tabby, and being around for them was far more important to him than trying for fame and fortune. He played a number of different clubs for varying lengths of time until 1972 when he started at the Acorn. There he played from 9 pm- 4 am (5 on Saturdays) six nights a week for almost two decades.

Priority number two was his religion. Fans who heard Buddy’s bawdy songs and occasional crude jokes on Saturday night probably never guessed that Buddy taught Sunday school. He was a devout Catholic who took mass on a daily basis. For the last several years of his life he led his congregation in the Stations of the Cross. And for all the interesting words I heard Buddy use during the nearly 40 years I knew him, I never heard him take the name of the Lord in vain.

Priority number two was his religion. Fans who heard Buddy’s bawdy songs and occasional crude jokes on Saturday night probably never guessed that Buddy taught Sunday school. He was a devout Catholic who took mass on a daily basis. For the last several years of his life he led his congregation in the Stations of the Cross. And for all the interesting words I heard Buddy use during the nearly 40 years I knew him, I never heard him take the name of the Lord in vain.

Then there were his friends. For a man who worked six days a week, served his church and raised four children, he was never too busy to help a friend. Whether it was writing out a piece of sheet music, coaching someone through a song, putting in a good word to a bar owner about a musician or helping someone through a personal crisis, Buddy always found the time. I used to spend all my birthdays at the Acorn and later at the Coq d’Or until Buddy left there, not long after my 50th birthday. For the next eleven years he always made his way to my birthday party no matter where it was. That’s the kind of friend he was.

And there were all his other interests. Buddy was fascinated by all that went on in the world. He read two newspapers a day and devoured biographies and history books. His friend Dick Newman, Buddy and I would spend many of his breaks at the Acorn, sitting at the back table, discussing current events or some historical figure. I never met anyone who was so well versed in so many different areas.

That is not to say that Buddy neglected his entertaining. He loved it and he never stopped learning new songs. He practiced daily on a cardboard keyboard just to keep his fingers nimble.

In 1990, the Acorn’s building was sold to an upscale clothier. He moved across the street to the Coq d’Or room in the Drake. He did not like it. It was smoky, noisy and set up in a way where he was never able to get the full crowd’s attention. Still, he lasted until 1997 when he decided he’d had enough. On September 12, 1997, Chicago’s Mayor, Richard M. Daly, officially proclaimed Buddy Charles Day as he retired.

In 1990, the Acorn’s building was sold to an upscale clothier. He moved across the street to the Coq d’Or room in the Drake. He did not like it. It was smoky, noisy and set up in a way where he was never able to get the full crowd’s attention. Still, he lasted until 1997 when he decided he’d had enough. On September 12, 1997, Chicago’s Mayor, Richard M. Daly, officially proclaimed Buddy Charles Day as he retired.

Retirement probably saved his life. Finally taking time to get a full physical it was discovered he had some heart problems that required surgery. A few months after surgery, feeling refreshed, Buddy unretired. He began playing local clubs and spent some time at The Big House and Cornelia’s. He worked with good friends Mark and Anne Burnell. He did a couple of shows in Milwaukee with Jeanne Scherkenbach.

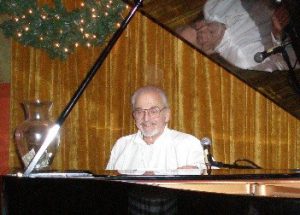

Then he was invited to play at Chambers and it was the perfect situation for him. Only minutes from his home in Morton Grove, he played one or two nights a week. His wife and one or more of the children would always be there. His friends would show up. All his top priorities were being met.

For the last couple of years of his life Buddy fought with leukemia. He was sometimes so worn out and tired he didn’t feel like moving. Still, until the last two weeks of his life, he showed up every night he was scheduled. And as beat as he was, when he started playing, energy started to grow, and at some point in the night you would see him lean back with his eyes closed, with music flowing out of his fingers, racing across the keyboard and into the hearts of his audience.

by Scott Urban

Note from the editor: To our cabaret community it seems Buddy Charles’ artistic legacy has only grown since his passing in 2008, thanks, in part, to his friends like Scott Urban who meet annually to hold a party in his honor. Although those gatherings have been postponed by pandemic restrictions, we look forward to their eventual return.