This is the second part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part One here.

This is the second part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part One here.

June Skinner Sawyers is an editor and journalist who writes frequently about music and the arts. Her publications include Cabaret FAQ and Chicago Sketches: Urban Tales, Stories, and Legends from Chicago History. She was a regular contributor to the Chicago Tribune, for which she wrote a nightlife column for three years and is the editor of several literary anthologies. Here is part two of a revised and up-dated edition of that history.

—Daniel Johnson

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 had a profound effect on Chicago cabarets. The Illinois state legislators,” writes Jim Elledge, “put a stranglehold of regulations on the cabarets, and the city fathers took the opportunity to send police to raid and board them up.” A few years earlier, in 1928, the federal crackdown on public consumption of alcohol “devastated the Chicago cabaret scene: 250 cabaret entertainers and 200 musicians had lost their jobs,” notes William Howland Kenney.

It took many more years for the cabaret scene to get back on its feet. The live music scene in Chicago soon migrated to big bands and orchestra’s featuring social dancing. Even during the Great Depression these events were widely enjoyed by the public via live radio broadcasts. During this period band singers became more prominent and began a trend toward celebrity singing stars of later times.

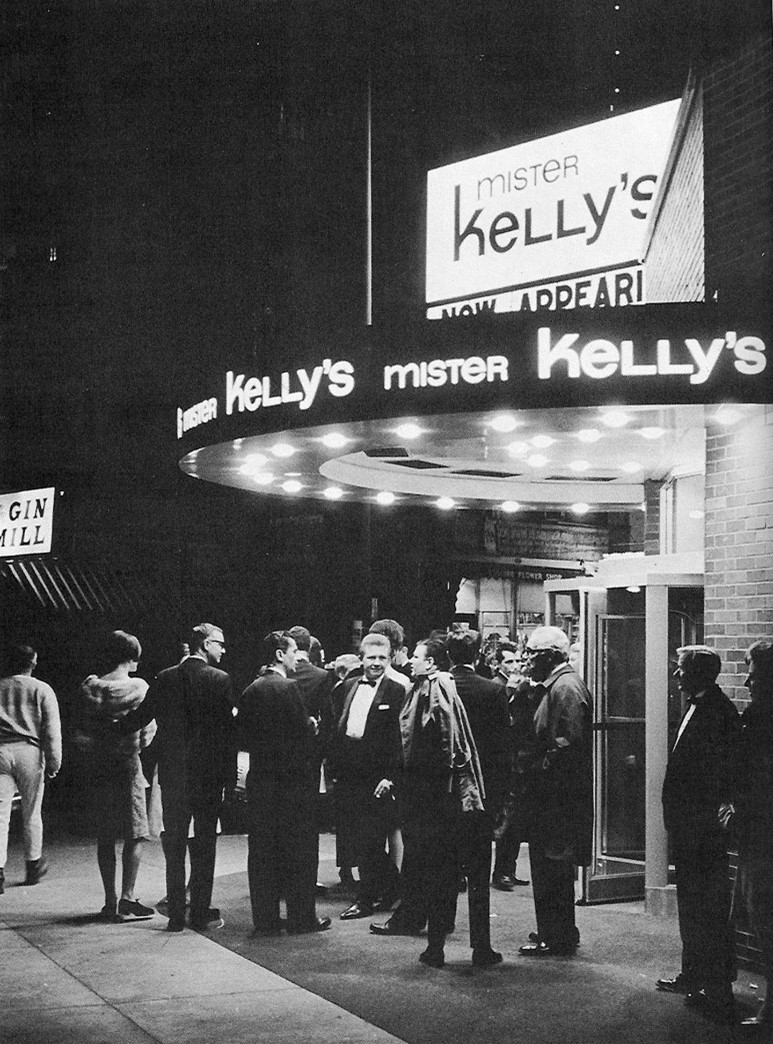

During the post-World War II era new cabarets opened, especially at or near Rush Street. Probably the most popular at the time was Mister Kelly’s, owned and operated by the Marienthal brothers.

George and Oscar Marienthal grew up in Hyde Park on Chicago’s South Side. They opened their first place, a diner called the Fort Dearborn Grill, in 1946 in the London Guarantee Building at the corner of Michigan and Wacker. They spruced up the place and eventually changed the name to the London House. By 1951 they began featuring live jazz seven nights a week in a cabaret-style setting.

George and Oscar Marienthal grew up in Hyde Park on Chicago’s South Side. They opened their first place, a diner called the Fort Dearborn Grill, in 1946 in the London Guarantee Building at the corner of Michigan and Wacker. They spruced up the place and eventually changed the name to the London House. By 1951 they began featuring live jazz seven nights a week in a cabaret-style setting.

A few years later they opened Mister Kelly’s — named after the club’s first manager, Pat Kelly — at Rush and Bellevue. Although it served food, what set it apart was its top-tier performers, from Barbra Streisand to Bette Midler.

The club was destroyed in a 1955 fire but rebuilt and reopened in August 1956. By the late 1950s, various entertainers recorded live albums there, including Ella Fitzgerald, Buddy Greco, Sarah Vaughan, Della Reese, and Anita O’Day.

Fire again destroyed the club in February 1966. And once again, it reopened — in May 1967. The club eventually closed in August 1975.

Another Marienthal club was the Happy Medium that opened in 1960 at Rush and Delaware. It was both a theatre and a live music club. Still another classic post-World War II cabaret was the Gold Star Sardine Bar at 680 N. Lake Shore Drive. The Gold Star Sardine Bar used to be located at the 666 N. Lake Shore Drive building (renamed 680 to avoid the satanic connotation) at the corner of Erie and Lake Shore Drive.

The Gold Star lived up to its name since it could only hold about 50 people and patrons usually were packed in like sardines. On weekends, daunting lines of patrons seeking live jazz and torch music would stretch down the block.

Wrote Dennis McCarthy in his classic The Great Chicago Bar & Saloon Guide (1985): “Inside a beautifully old building you will find the Gold Star, an expensive lounge decorated in a modern imitation of 1940s New York hotel bar chic. The place is tiny, dimly lit and decorated with a series of photos from the 1940s which, except for their historical association, seem to have no relevance.”

In 1954, Herman Roberts founded Roberts Show Lounge at 6622 S. Parkway (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), where he booked the likes of Nat “King” Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Count Basie, and Lionel Hampton as well as R&B and soul performers such as Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson. The South Side club was an elegant venue that featured mostly black entertainers although Roberts occasionally booked top white talent too, including Tony Bennett and Gene Krupa. The club closed in 1961.

In 1954, Herman Roberts founded Roberts Show Lounge at 6622 S. Parkway (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), where he booked the likes of Nat “King” Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Count Basie, and Lionel Hampton as well as R&B and soul performers such as Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson. The South Side club was an elegant venue that featured mostly black entertainers although Roberts occasionally booked top white talent too, including Tony Bennett and Gene Krupa. The club closed in 1961.

Roberts became almost as famous as the performers he booked. Indeed, it was said that he knew everyone and everyone knew him. He knew what he liked and he knew which acts would pull people in. He also had his own idea of what constituted a nightclub. A real nightclub, he told James Porter in the Chicago Reader in 2014, required an “emcee, chorus line, a full cabaret show.”

During the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, Chicago boasted several excellent clubs that specialized in cabaret.

Gentry of Chicago was established in March of 1983 at 712 N. Rush Street by Alden Jones catering to gay professionals and out-of-towners. The original location, housed in an old three-story townhouse, featured a martini/conversation bar with a large Swarovski crystal chandelier as its focal point, with a 32-seat cabaret room and an upstairs dining room. There was also a Lakeview branch at 3320 N. Halsted Street. In

February of 1997 the 712 North Rush building was sold and Gentry’s lease was not renewed. A new owner, David Edwards, relocated the club he had purchased in November of 1988. Gentry customers were without a downtown home until the new location was opened Dec. 23, 1997.

Gentry of Chicago’s River North location at 440 North State Street also provided popular cabaret entertainment. The first show of the evening began at 5:30 p.m. weekdays; main entertainment ran from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. nightly with an open-mic night on Sundays. Tucked between the two bars were more intimate nooks with tables or stuffed chairs. A video bar downstairs with an up-tempo atmosphere cranked high-energy dance videos, customers gathered around the bar and cocktail tables or tossed darts at two dart boards. Windy City Times reported the passing of Gentry owner David D. Edwards in February of 2005. The closure of his clubs followed sometime later.

Gentry of Chicago’s River North location at 440 North State Street also provided popular cabaret entertainment. The first show of the evening began at 5:30 p.m. weekdays; main entertainment ran from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. nightly with an open-mic night on Sundays. Tucked between the two bars were more intimate nooks with tables or stuffed chairs. A video bar downstairs with an up-tempo atmosphere cranked high-energy dance videos, customers gathered around the bar and cocktail tables or tossed darts at two dart boards. Windy City Times reported the passing of Gentry owner David D. Edwards in February of 2005. The closure of his clubs followed sometime later.

Many of today’s leaders in Chicago cabaret honed their skills entertaining at Gentry. For instance, Beckie Menzie (three-time After Dark Award Winner for Outstanding Cabaret Artist) often speaks fondly of her years as a regular. As she said recently, “When Gentry closed, I was one week short of starting my 20th year as the Sunday open mic host. I LOVED working at the Gentry and credit my 19 years there as the best school on how to learn to entertain a room and find your own artistic identity. Those Sunday nights at the Gentry on Rush would be the hangout for area theatre casts and people who just loved to sing. People would come into that club and never feel like they were a stranger and each night felt like a marvelous party. Because it was an intimate listening room it seemed much more like a cabaret room than a piano bar and really was the best of both.”

Parisian-style cabarets were not far from the thoughts of at least one Chicago cabaret owner. Bob Djahanguiri opened Toulouse on Division Street during the middle of a Chicago blizzard in 1979. The local cabaret singer Karen Mason — who now performs nationally — was the headliner that wintry night. Djahanguiri moved from his Division Street digs to a more upscale Lincoln Park address, along with Yvette and several other clubs featuring cabaret.

According to Achy Obejas of the Chicago Tribune, he designed the carpeting for the cabaret and “brought in a consistently interesting stable of singers, giving them uncommon support and promotion.” She also wrote this: “Once or twice, there have been reports that cabaret is on the rise again, then that it’s again passe. In either case, Toulouse is always mentioned.”

According to Achy Obejas of the Chicago Tribune, he designed the carpeting for the cabaret and “brought in a consistently interesting stable of singers, giving them uncommon support and promotion.” She also wrote this: “Once or twice, there have been reports that cabaret is on the rise again, then that it’s again passe. In either case, Toulouse is always mentioned.”

Anne Burnell recalls working for Djahanguiri when she first moved to Chicago. Journalist Rick Kogan wrote a piece for the Chicago Tribune recounting how she was “discovered” at Yvette. SINGER LIVES UP TO HER CHANCE `DISCOVERY` – Chicago Tribune

Burnell says the piano players at Yvette and Toulouse introduced her around town to hear all the best people – Audrey Morris, Dave Green, Buddy Charles, and many more, and she learned a lot in her Djahanguiri days. −Editor

That was in the 1980s. Toulouse is long gone, of course, but cabaret in all its forms is still here. By 2018, Chicago was home to not only cabarets but also piano bars and burlesque clubs.

Perhaps the best-known cabaret — certainly the oldest still-existing — is Davenport’s at 1383 N. Milwaukee Avenue. When Bill Davenport, Sue Berry, and Donna Kirchman opened Davenport’s in 1998 in the Wicker Park neighborhood on the Northwest side, they knew it would be a struggle. (Davenport has since relocated to Palm Springs; Berry and Kirchman bought him out.)

It has two rooms: the bigger lounge in the back accommodates 75; the piano bar upfront, 50. Located on a commercial strip in a funky neighborhood, the view from the window is far from glamorous — a Walgreen’s is located directly across the street — but it presents the best of local and national talent, from the afore- mentioned Karen Mason to Andrea Marcovicci. Best, in the piano bar you can hear singers for free, singers with voices that really belong on Broadway.

It has two rooms: the bigger lounge in the back accommodates 75; the piano bar upfront, 50. Located on a commercial strip in a funky neighborhood, the view from the window is far from glamorous — a Walgreen’s is located directly across the street — but it presents the best of local and national talent, from the afore- mentioned Karen Mason to Andrea Marcovicci. Best, in the piano bar you can hear singers for free, singers with voices that really belong on Broadway.

Speaking of piano bars, theatre historian John Kenrick offers one of the best descriptions of one: “A piano bar is a hybrid creature: part performance space, part living room, part cruise-a-thon, and part saloon. The bar is there to sell drinks, the pianist is there to perform, and the crowd is there to sing, listen, drink and socialize.

“All of this means that it’s impossible to predict what a given evening’s chemistry will be, even if most of the people on hand are regular customers . . . While every factor counts, the most important issue is the person at the piano.”

“The pianist determines the type of music, the style of performance, and the general tone of the evening. The experienced piano bar player knows how to take genial control of most any situation and generally keep the party going.”

There are a few others beside Davenports left. The Redhead Piano Bar, located in the basement of a River North brownstone, offers live piano music every night. A large rectangular bar sits in the middle of the room. The performers take requests, which typically can range from Abba to, of course, Billy Joel — the Piano Man himself.

Indeed, a black and white photo of Joel sits behind the piano. But it is also the kind of place where the Beatles “Lady Madonna” seamlessly segues into, say, Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.” You never know what you might hear at a piano bar. There is also an extensive martini menu. Best of all though is the neon sign: a redhead with a 1960s-era do looks over her shoulder with a flirtatious wink. She was modeled after a real person, Eileen Wolcoff, who not only founded the club, she WAS the redhead. She died in June 2017.

Indeed, a black and white photo of Joel sits behind the piano. But it is also the kind of place where the Beatles “Lady Madonna” seamlessly segues into, say, Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.” You never know what you might hear at a piano bar. There is also an extensive martini menu. Best of all though is the neon sign: a redhead with a 1960s-era do looks over her shoulder with a flirtatious wink. She was modeled after a real person, Eileen Wolcoff, who not only founded the club, she WAS the redhead. She died in June 2017.

Even older than the Redhead is the Zebra Lounge Piano Bar at 1220 N. State Parkway; it’s been around since the Prohibition era — since 1929 to be exact, featuring live piano players seven nights a week.

In Chicago’s theatre district, Covid-19 restrictions allowing, one may check out Petterino’s Monday Night Live hosted by Denise McGowan Tracy with Beckie Menzie usually at the piano. As blogger Nina Ivon writes: “Denise is an extraordinarily talented singer and an amazing event planner . . . she knows everyone! Do catch her at Petterino’s Monday Night Live, you won’t be disappointed and you may well hear many other talented performers . . . from one of the many Chicago’s stage productions . . . you will have a fantastic evening of entertainment along with your always yummy food and drink selections at the popular Petterino’s.”

Recently, there has been a revival of interest in old-fashioned cabaret-style programs such as burlesque. The term derives from the Italian burlesco, with its connotations to ridicule or mock. Modeled after the then-popular minstrel shows, burlesque was a form of entertainment intended to make light of serious topics or subjects.

The famous Moulin Rouge in Paris featured — and still features — loosely strung together acts, from contortionists to performers. In the US, burlesque refers to performances that offer a risqué variety show format. These forms of burlesque were popular in clubs and cabarets as well as in theatres and often featured bawdy comedy and striptease acts.

Around the turn of the 20th century, for example, there were a few national burlesque circuits that competed with the vaudeville circuit.

One of the best known was Minsky’s, which had venues in various cities throughout the US. Indeed, most of Chicago’s burlesque theaters were located on the periphery of downtown, especially along South State Street between Van Buren and Polk Streets and along West Madison Street near Halsted Street as well as the Levee district near 22nd and State.

One of the best known was Minsky’s, which had venues in various cities throughout the US. Indeed, most of Chicago’s burlesque theaters were located on the periphery of downtown, especially along South State Street between Van Buren and Polk Streets and along West Madison Street near Halsted Street as well as the Levee district near 22nd and State.

In addition to Minsky’s, other burlesque theaters included the Gem at 450 South State Street on the site now occupied by Harold Washington Library; the Trocadero at 414 South State; and the Rialto at State and Van Buren, which also operated as a vaudeville house and which was operated by Harold Minsky. In the 1960s it changed from burlesque to adult movies.

One of the best known of the burlesque strippers in Chicago was Sally Rand, famous for her ostrich feather fan dance. Her most legendary, and notorious, appearance in Chicago took place at the 1933 World’s Fair, or Century of Progress, as it was known. She would hold two giant fans made of ostrich feathers in front of her naked body. A musical ensemble of some sort would usually play a classical piece such as DeBussy’s “Claire de Lune” to lend a touch of class.

Among the newest cabaret-style venues is Bordel in Wicker Park, which combines elements of burlesque and touches of vaudeville. On Friday nights it has presented what it called a ‘secret speakeasy’ — vaudeville with a rotating cast of burlesque dancers, magicians, and palm/tarot card readers.

Kiss Kiss Cabaret at the recently closed Uptown Underground also presented old-fashioned burlesque shows on Wednesday nights, as well as cabaret acts, from snarky hosts (sort of a modern equivalent of Joel Grey’s Master of Ceremonies in the movie Cabaret) to jugglers to musicians to balloon-animal swallowers.

In 2017, Reggies at 21st and State presented an eclectic program called “The Midnight Cabaret” that included dancing, burlesque, vaudeville, and even a freak show (shades of Coney Island).

And then there is the Drifter, housed in the basement of the Green Door Tavern, at 676 N. Orleans, the oldest pub in Chicago. It features an old-fashioned cocktail bar with a drink list printed on tarot cards. Its tiny stage presented burlesque acts, magicians, jugglers, short films — anything and everything. One Halloween evening it presented The Lost Night, a 1920s style Hollywood party in what was billed as a séance cabaret.

Until the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily shut it down, Drew’s on Halsted (3201 N. Halsted Street) presented live music and cabaret in a supper-club atmosphere. In 2019, the Lakeview East Chamber of Commerce awarded Drew’s the Best New Concept for their “Cabaret Nights.”

Jonathan Lewis in Brand New Day at Le Piano

In 2018, Le Piano opened in the former space of Theo Ubique Cabaret Theatre (for more, see below). Owner and veteran Chicago jazz musician Chad Willetts presented live jazz in a gorgeous Parisian-style café setting.

Another example of cabaret is the so-called cabaret theatre, Theo Ubique, which, before moving to its new location in Evanston, presented its exquisite shows in its tiny storefront space in Rogers Park at No Exit (which in its former life was a well-known coffeehouse/folk club).

Theo Ubique has presented not only musical theatre (such as Sweeney Todd and Cabaret) but also intimate revues such as “A Kurt Weill Cabaret” and Jacques Brel’s “Lonesome Losers of the Night.” At left is a rendering of their new cabaret theatre in Evanston.

Theo Ubique has presented not only musical theatre (such as Sweeney Todd and Cabaret) but also intimate revues such as “A Kurt Weill Cabaret” and Jacques Brel’s “Lonesome Losers of the Night.” At left is a rendering of their new cabaret theatre in Evanston.

Cabaret has often been called a “lost” art form. It will never be part of mainstream society in the way of, say, cinema or television or popular music. It probably always will be “beyond the margins,” as former Chicago Tribune music critic Howard Reich says.

But it lives on.

−by June Skinner Sawyers, graphics by Charles Troy

This is the second part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part One here.

This is the second part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part One here.