This is the first part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part Two here.

This is the first part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part Two here.

June Skinner Sawyers is an editor and journalist who writes frequently about music and the arts. Her publications include Cabaret FAQ and Chicago Sketches: Urban Tales, Stories, and Legends from Chicago History. She was a regular contributor to the Chicago Tribune, for which she wrote a nightlife column for three years and is the editor of several literary anthologies. Here is a revised and up-dated edition of that history.

—Daniel Johnson

Cabaret, the art form, and the city of Chicago have grown up together. And like all relationships, it’s seen its share of ups and downs and growing pains on its way to a certain type of maturity.

In Chicago, during the Ragtime era, cabarets allowed men and women of different

social backgrounds to mingle, especially during the dance craze from around 1910 and into the 1920s. Cabarets became public meeting grounds, places where self-expression was allowable, at least on the dance floor. They were also among the first places in the city that allowed women to drink in public.

Since the early decades of the twentieth century, cabarets and nightclubs have been concentrated primarily, but not exclusively, in three areas: the Loop, especially along Randolph Street; the Near North Side, such as the old neighborhood once called Towertown and, later, on Rush Street; and on the South Side, in the Levee District and Bronzeville neighborhood.

The types of cabaret that existed in the city—and still exist—varied, from traditional cabaret to burlesque to drag shows featuring female impersonators. The golden years of the cabaret era in Chicago occurred during the World War I and post-World War I eras—and during that time, one North Side neighborhood dominated the scene: Towertown.

Towertown was the Bohemian center of Chicago during the teens, 1920s, and even into the 30s. Towertown was located in the shadow of the historic Water Tower, which is how it earned its colorful nickname. It consisted of a demi-monde of furnished rooms and walk-up apartments but also various restaurants, theaters, cafes, saloons, and, of course, cabarets.

North Clark Street separated Towertown from Little Sicily on the west. According to Jim Elledge, author of the 2018 book The Boys of Fairy Town, this stretch of Clark Street had nearly 60 saloons, almost 40 restaurants, and 20 cabarets.

The residents of the neighborhood included artists, students, the intelligentsia, and assorted slummers and weekend bohemians. Specificially, Towertown was populated by people on the fringe of ‘polite’ society: gays and lesbians, and nonconformists and iconoclasts of every social persuasion. Like Greenwich Village at the time, it was cheap and thus affordable to people whose income was precarious at best.

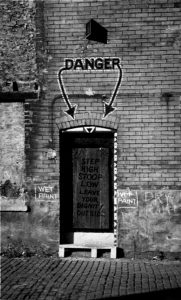

Not surprisingly, Towertown had a rich nightlife. None of the venues were more famous, or notorious, than the Dil Pickle Club, located just off Washington Square Park, across from the Newberry Library on a tiny street called Tooker Place also known as Tooker Alley and sometimes listed as being at 863 or 867½ North Dearborn Street. The address seemed unimportant — what was distinctive was the nondescript door with the sign “Step High / Stoop Low / Leave Your Dignity Outside.” The club was founded by Jack Jones, a Canadian-born miner and organizer and one of the most influential inhabitants of post-World War I bohemian Chicago.

Initially Jones had opened a humble coffeehouse on Locust Street, patronized mostly by laborers and labor leaders. In 1916, he moved to larger quarters at 18 Tooker Place, within hailing distance of Washington Square or Bughouse Square, as it was known. Bughouse Square was Chicago’s version of the Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park.

Initially Jones had opened a humble coffeehouse on Locust Street, patronized mostly by laborers and labor leaders. In 1916, he moved to larger quarters at 18 Tooker Place, within hailing distance of Washington Square or Bughouse Square, as it was known. Bughouse Square was Chicago’s version of the Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park.

Artists, poets, labor organizers, reds and capitalists, the intelligentsia, philosophers, thieves and hobos, the working class and the upper crust—everyone was welcome at Jones’ club. The Dil Pickle also attracted famous speakers, from lawyer Clarence Darrow and writer Sherwood Anderson to poet Carl Sandburg and socialist politician Eugene Debs.

No matter what night of the week, the audience could listen to the famous, the infamous, hear lectures, and watch performers—all in a carnivalesque, cabaret-style atmosphere. The Pickle, for example, hosted free love lectures, masked balls such as “A Night in Bohemia,” or anti-war dances, especially during World War I.

Among the cabarets of Towertown was Ye Black Cat, its name perhaps inspired by the original cabaret in Paris in 1881. It was a semi-private club for more affluent members of the gay community before its luster waned and it became more known for its seedy drag shows and the homeless population that it catered to.

Another popular place was the Green Mask, ostensibly a tearoom but one that had a strong bohemian, cabaret-like vibe. Located in the basement of a building at Grand and State at the southern edge of Towertown, it was also an after-hours hangout for jazz musicians and an early venue for jazz poetry readings. The poet Kenneth Rexroth worked there. Maxwell Bodenheim, Vachel Lindsay, and Rexroth himself read poetry at the Mask, sometimes accompanied by drummers or pianists.

Nearby, the Erie Cabaret at the corner of Clark and Erie, whose name inspired a current day restaurant, was the home to the female impersonator Frances Carrick, one of Towertown’s most famous, and singular, residents.

Another popular Towertown cabaret was Bert Kelly’s Stables, located at 431 N. Rush Street. Legendary jazz musicians performed at the club, such as the cornet player and bandleader Joe “King” Oliver and the great clarinet player Johnny Dodds, who led a small house band in the 1920s.

Another popular Towertown cabaret was Bert Kelly’s Stables, located at 431 N. Rush Street. Legendary jazz musicians performed at the club, such as the cornet player and bandleader Joe “King” Oliver and the great clarinet player Johnny Dodds, who led a small house band in the 1920s.

But Towertown wasn’t the only North Side neighborhood that was home to cabarets. Other North Side venues included Rainbo Gardens at Clark and Lawrence, which boasted a stage that opened out into its namesake exterior gardens and which featured various forms of entertainment and vaudeville numbers.

But probably the most famous club was the Green Mill, which presented top acts. The Green Mill opened in 1907 and is the longest continuously operating nightclub in Chicago. Its name is a deliberate reference to the Moulin Rouge, which means Red Mill. It warrants its own history, but one anecdote is worth mentioning.

In 1927, the singer and comedian Joe E. Lewis refused Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn—one of Al Capone’s henchman—to renew his contract to perform at the Green Mill (which was partly owned by Capone). Lewis had been offered more money by a rival gang at the New Rendezvous, another cabaret. He was rewarded for this act of disloyalty by having his throat cut. Lewis survived the assault. The incident was captured in the 1961 film The Joker Is Wild, which starred Frank Sinatra, who also happened to be a friend of Lewis.

Speaking of gangs and gangland vice, some of the most notorious as well as popular cabarets were in an area of town referred to as the Levee: Chicago’s Red Light District. It roughly ran along South Wabash between Van Buren and 22nd Street. It is better known today as being a part of the South Loop, veering towards Chinatown. The city’s most famous brothel, the notorious Everleigh Club at 21st Street and Dearborn Avenue, was located here, housed in a classic Chicago three-story brownstone.

A notable—if not notorious—venue in the area was known as Freiberg’s Dance Hall, on 22nd Street, which also happened to be a brothel; it was managed by Ike Bloom who earned the moniker of “the King of the Brothels.” When Freiberg’s closed, Bloom opened the equally successful Midnight Frolics known for its “girlie” entertainment.

After countless police raids, grand jury investigations, vice commission reports, and various denunciations by reformers, the Levee was shut down by Mayor Carter Harrison in 1912.

But despite the shutdown of the Levee, the legitimate cabarets lived on, even as they skirted the periphery of the law due to ownership by known gang members.

One of the cabarets in the area was owned by the gang leader “Big Jim” Colosimo. In 1910, Colosimo opened his famous cabaret at 2126 S. Wabash Avenue. It was known for its good music, excellent food, and fine wine. It was the place to go after the rest of the city went to bed.

Big Jim attracted a diverse clientele: thieves and gamblers, as well as, millionaires and merchants, bankers and school teachers, and even the chief of police. It became so popular that Colosimo built an annex next door. One section would stay open until one in the morning, in observance of the city’s tavern-closing law, but patrons then moved into another room to continue their partying ways. One poster boasted that it was open all night, with dancing from 7pm until 4am. Colosimo’s in fact was ‘Where Bohemia Meets,’ where you could ‘dance when you like.’

Into this setting one day walked in Dale Winter, a sweet-voiced choir singer from Grand Rapids, Michigan—an innocent waif in the big city. Big Jim quickly fell in love with her even though he was still married, which turned out to be a minor inconvenience. Before you could say ‘Al Capone,’ Winter was given star billing at his café along with a few choice singing lessons.

After Colosimo sought an uncontested divorce from his first wife, this oddest of couples eloped and enjoyed a two-week honeymoon. But all good things must come to an end. In May 1920, Colosimo was shot to death in his own café. He fell face down on the porcelain floor, dead at age 49. Now a widow after being married for only a few weeks, Winter left Chicago, Colosimo’s eventually went out of business, and was turned into —what else? — a parking lot.

Downtown also had its share of cabarets and cabaret-style venues. Beginning in the 1920s and continuing in the 1930s, the Loop hotels had nightclubs and cabarets that featured dancing, floor shows, and live radio broadcasts. These included the Boulevard Room of the Stevens Hotel, which later became the Conrad Hilton, the Palmer House’s Empire Room, and the Sherman Hotel’s College Inn. The Blackstone, LaSalle, and Bismarck hotels also featured entertainment.

Also located in or near the Loop were such clubs and cabarets as the Blackhawk Restaurant at 139 North Wabash Avenue and the Hotel Morrison’s Terrace Room, as well as the Moulin Rouge Café at 416 South Wabash Avenue.

Among the most popular was Mike Fritzel’s Friars’ Inn located in a basement at 343 South Wabash. Billed as the ‘Land of Bohemia Where Good Fellows Get Together,’ it featured the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, among other performers.

Chez Paree at 610 Fairbanks Court was especially known for its glamorous atmosphere, elaborate dance numbers, and top-class entertainers from Armstrong to Fitzgerald to Sinatra. Operating from 1932 until 1960, it attracted young and old, socialites and wise guys, as one description said. But Chicago’s love of cabaret reached south of the Chez Paree, and south of the Levee.

Chez Paree at 610 Fairbanks Court was especially known for its glamorous atmosphere, elaborate dance numbers, and top-class entertainers from Armstrong to Fitzgerald to Sinatra. Operating from 1932 until 1960, it attracted young and old, socialites and wise guys, as one description said. But Chicago’s love of cabaret reached south of the Chez Paree, and south of the Levee.

Bronzeville on the South Side was especially known for its cabarets and clubs, which headlined jazz combos along with song and dance specialties and blues singers. By the early 1920s, in fact, numerous places had opened on the Stroll, as the South Side amusement zone along 35th and State Streets was called.

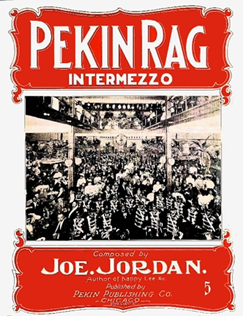

The Pekin Inn, at 2700 South State Street, was a turn of the twentieth century gambling hall, theater, and nightclub/cabaret. Considered the most important club on the South Side at the time, it was the first black-owned club in the country.

The Pekin Inn, at 2700 South State Street, was a turn of the twentieth century gambling hall, theater, and nightclub/cabaret. Considered the most important club on the South Side at the time, it was the first black-owned club in the country.

Among the most popular Jazz Age cabarets were the so called black and tan clubs, which consisted of entertainment by black performers, but that catered to both blacks and whites. Here, unlike anywhere else in segregated Chicago, the races could interact with one another: talking, dancing, listening, even flirting.

“Whites could venture into black cabarets, but blacks could not enter most nightclubs or dance halls in white Chicago, not even those white establishments where black orchestras provided the music,” writes historian William Howland Kenney.

Another venue, the Sunset Cafe, later renamed the Grand Terrace Café, was one of the most important venues during the Jazz Age, hosting many Jazz era greats. Built in 1909 as a garage, it was converted to a nightclub and opened with about 100 tables, a bandstand, and a full dance floor. The white-owned club was a black and tan. Al Capone reportedly acquired a one-quarter interest in the venue. The actual building received City of Chicago landmark status in September 1998. Until 2017 it functioned as an Ace Hardware store. Some of the original murals from the Sunset remain on the walls.

Diagonally across the street from the Sunset was the Plantation Café, at 338 East 35th Street near Calumet Avenue. Joe Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators, an important jazz combo, played there often.

In the late 1930s, the most popular of the gay-owned cabarets in Bronzeville were the Club De Lisa, at 5516 South State Street, and the Cabin Inn, at 3119 South Cottage Grove Avenue.

In the late 1930s, the most popular of the gay-owned cabarets in Bronzeville were the Club De Lisa, at 5516 South State Street, and the Cabin Inn, at 3119 South Cottage Grove Avenue.

Bronzeville’s middle class especially liked Club De Lisa, considered the largest and most important nightclub in the African American community from the 1930s to the 1950s.

The Cabin Inn billed itself as the South Side’s “Oddest Nite Club.” It was known for its female impersonators. Given the nightly drag shows it presented, the Cabin Inn attracted a different clientele from most Bronzeville cabarets. Still, it appealed to both black and white working classes.

Also in Bronzeville was the Dreamland Café, at 3520 S. State Street, another black and tan cabaret, where Joe “King” Oliver played gigs, as well as Jimmy Noone and Sidney Bechet. In the early 1920s Dreamland (according to the Chicago Defender) hosted young Alberta Hunter, a songbird later famous in Europe, as well as Louis Armstrong with his wife Lil Hardin.

More elaborate was the Regal Theatre, at 4719 South King Drive, which was open from 1928 and 1973. It presented films accompanied by African American stage performers and a full floor show with the Regalette dancers.

And then there was the short-lived Café de Champion at 41 W. 31st Street, among the most famous of the South Side cabarets and also a black and tan club. Boxer Jack Johnson opened it in July 1912, two years after he had become the first black heavyweight champion of the world.

Johnson made good money and he wanted to make sure that his club reflected his elevated status. According to a report in the Chicago Tribune, the venue had monogrammed spittoons in solid silver, $15,000 worth of oil paintings of Johnson and his family, and a mosaic inlaid floor tile. It boasted white-gloved waiters in evening clothes and a beautiful mahogany bar. The Pompeiian Room, where the music and dancing was held, was said to hold hundreds of people.

Johnson was an iconic figure who spoke his mind and did want he wanted to do, including marrying three white women. Three months after the club opened, Johnson’s wife, Etta, committed suicide in their apartment above the café while patrons partied below. Things only got worse.

His second marriage to 19-year-old Lucille Cameron caused an uproar when Cameron’s mother accused Johnson of violating the Mann Act, a 1910 law that banned the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Johnson was convicted of the charge, sentenced to a year in prison, and fined $10,000. He fled to Canada and then to Europe before finally returning to the US and surrendering to authorities in Los Angeles in 1920.

This episode is the basis for the popular 1970 movie, The Great White Hope, that made James Earl Jones a star. As for Jack Johnson’s popular cabaret, it closed after he fled the country, having lasted only a few months.

Bronzeville is important for another reason. The Chicago-Paris connection can be traced back to the cabarets of Bronzeville. The great Chicago painter Archibald Motley spent a year studying in Paris in 1929 but before that he captured the vibrant Bronzeville nightlife in such paintings as his 1927 painting “Stomp.” He also depicted bohemian life in Paris in “Blues (Paris)” in 1929.

But among the most singular figures in Chicago-Paris cabaret history is the African-American dancer, singer, and club owner Bricktop. Born Ada Louise Smith, she earned her nickname because of her red hair and freckles. Bricktop grew up in Chicago and began performing at the tender age of five, playing the role of Harry in Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the Haymarket Theatre. By the time she was a teenager, she was performing in the chorus at the Pekin Inn in Bronzeville.

She moved to Paris in the mid-1920s where she not only performed in the Parisian cabarets, she owned them, including Le Grand Duc and Chez Bricktop. Everyone went to Bricktop’s, from Ellington to Josephine Baker to Hemingway and Fitzgerald. She soon became the undisputed queen of Montmartre. In her 1983 autobiography, she observed that Montmartre had “as many cafes and dance halls and bordellos as . . . State

Street in Chicago.”

Dance styles during the heyday of the Jazz Age cabaret era largely reflected middle-class white taste. Customers would emulate the male dancers they saw on stage. Among the most influential in Chicago was Joe Frisco, known as a “jazz dancer.” He danced in clubs and on vaudeville stages to music performed by Bert Kelly’s Jazz Band and other musical ensembles.

Dance styles during the heyday of the Jazz Age cabaret era largely reflected middle-class white taste. Customers would emulate the male dancers they saw on stage. Among the most influential in Chicago was Joe Frisco, known as a “jazz dancer.” He danced in clubs and on vaudeville stages to music performed by Bert Kelly’s Jazz Band and other musical ensembles.

His typical outfit included a derby, cocked to one side, while he smoked a cigar, and cracked jokes out of the side of his mouth. He danced a dance called the hootchy-kootch, which consisted of a “slithering kind of shuffle,” as Martin Gottfried has described it. Is it any surprise that he influenced a young kid from the North Side of Chicago by the name of Bob Fosse?

Indeed, much of the seedy cabaret atmosphere that Fosse captured in his movies, especially Cabaret and All That Jazz, and in his stage choreography, came from his real-life experiences while growing up in Chicago. He was inspired by the strip tease dancers he saw in clubs like the Silver Cloud on Milwaukee Avenue, the Gaiety Village on Western Avenue, and the Cuban Village on Wabash Avenue.

Fosse was considered the “good boy” in the family. “My older brother had been in trouble—nothing serious,” he once told Chicago Sun-Times theatre critic Glenna Syse. “Stealing cars for a joyride, you know. I was not allowed to get a bad mark or swear around the house. I don’t know how much living up to those standards screwed up my personality but I’m sure it did . . .”

Fosse played “in every joint” in Chicago that would take him. “All the terrible theaters,” he once told Variety. “I remember the first place, the Silver Cloud. They had the strip teasers, the comic and me. I would dance. When the war came along, all the comics had to go. I became the youngest emcee in Chicago. I copied my dance act from anybody I could steal from. Astaire . . .”

Fosse would refer to his “strange, schizophrenic childhood” as being “a pull between Sunday School and my wicked underground life . . ,” he told Syse. Such experiences, he said, left its share of scars. “I think it’s done me a lot of harm, being exposed to things that early that I shouldn’t have been exposed to . . . it left some scar that I have not quite been able to figure out.”

The Fosse Look is known for its contradictions: elegant yet funky, sensual yet witty, rhythmic yet lyrical. In addition to Frisco, other influences included Balanchine, Nijinsky, Jerome Robbins, Fred Astaire, and Jack Cole, as well as baseball, boxing, and horse-racing. Fosse’s style was so personal, so singular, so idiosyncratic that it can be described in a specific way: his choreography was inspired by the way real people moved in daily life.

The Fosse Look is known for its contradictions: elegant yet funky, sensual yet witty, rhythmic yet lyrical. In addition to Frisco, other influences included Balanchine, Nijinsky, Jerome Robbins, Fred Astaire, and Jack Cole, as well as baseball, boxing, and horse-racing. Fosse’s style was so personal, so singular, so idiosyncratic that it can be described in a specific way: his choreography was inspired by the way real people moved in daily life.

Even the Chicago weather had its effect on his dancing style. Ann Reinking, for example, once told Chicago Sun-Times theatre critic Hedy Weiss that Fosse always remembered the brutal Chicago winters of his childhood and youth. “He had this move in which you’d walk slow motion against the wind, your shoulders hunched, your head down, your hands holding your hat.”

Fosse and cabaret went together. Cabaret was in his blood.

—by June Skinner Sawyers, graphics by Charles Troy

This is the first part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part Two here.

This is the first part of the 2-part history of Chicago Cabaret. You can read A History of Chicago Cabaret Part Two here.