This series is meant to help members understand the basics of what can be an intimidating subject: sound. It is not meant to be a crash course in sound engineering. I promise not to get too technical, and there is no math, so don’t get scared. [My qualifications: I hold a degree in music production and audio engineering from Berklee College of Music and have logged many hours working in sound, including nine months at the New England Conservatory of Music.]

Why do I need to know about this stuff?

- The more you know about sound, the better you can communicate with the sound person.

- Knowledge is power. The more you understand all the elements of live performance, the better your performances will be.

Won’t the sound person take care of it?

- Not necessarily. Some venues have good sound people. Some have people that can run a mixer but really don’t know anything about creating good sound. Sometimes you are completely on your own. So…

Part 1 – Vocal Microphones

There are two main types of microphones: Dynamic and Condenser. Without getting into the technology of why and how they are different, here’s what you should know:

Dynamic mics are good general microphones. They have a decent sound and are very rugged and dependable. Because of this, they are used most often in live performance situations.

Condenser mics have generally superior sound quality, but they are more delicate and more expensive than dynamic mics. They are most often used in recording studios and in live applications where superior sound is required. Using them on the road is a risk, due to their fragile nature and the expense of replacing them.

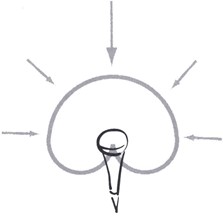

(mainly front pick-up)

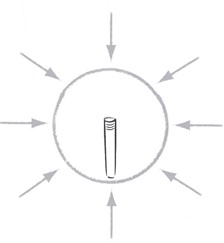

(equal pick-up all sides)

All microphones, no matter their type, have a specific ‘pick-up pattern.’ The pick-up pattern determines how a microphone ‘listens’ to sounds (i.e. from what directions it ‘hears’, from how far away, etc). Most vocal microphones are unidirectional microphones, meaning they are most sensitive to sound coming from the front (with some sensitivity to sound from the sides). Microphones that hang over a stage, and some hand-held vocal mics, are omnidirectional, meaning they are sensitive to sounds coming from all sides. These are the two patterns used most often in live vocal performance.

There are varying degrees for each type of pick-up pattern. The most directional mic out there, for instance, is called a shotgun microphone. It picks up sound only in the precise direction it is pointed but can pick up that sound from a long way off (picture those looooong microphones on the sidelines at football games that pick up no sideline noise whatsoever but capture every grunt and groan of the players 100 yards down field).

Vocal mics are not nearly as directional as shotgun mics and, thus, do not pick up from a great distance. Vocal microphones are close microphones. You can’t use standard vocal mics to amplify soloists, or small groups of people, standing more than 6-10 inches away. They just don’t work that way. [Nor are they meant to be piano mics, so if you see a piano with a couple of vocal mics set up underneath, this could mean you’re dealing with an unknowledgeable sound person (or it could mean the venue simply doesn’t have anything else).]

The absolute most common vocal mic in use today – and for a few decades now – is the Shure SM58. Clubs use this microphone because you can drop it or pound nails with it and it will still work. It’s a good all-purpose microphone, it’s durable, and it’s not expensive. It’s a jack of all trades microphone… but it’s a master at none. The problem with the SM58 is that it isn’t the greatest sounding vocal mic, and it has a great deal of handling noise. Every time you move your hand on the barrel of the mic, or adjust the mic stand, the audience hears it through the speakers. If you’re in the market for your own mic, there are many options that offer better sound quality with less handling noise and are still reasonably priced.

I leave you with three cardinal rules of microphone use:

- DO NOT tap or thump on a microphone to see if it’s on. If the sound is turned up high, thumping could damage a sensitive condenser mic. It will also blast the ears of everyone nearby and could cause feedback. INSTEAD, scratch it with your fingernail or talk into it.

- When leaving the stage or holding your microphone at rest, DO NOT point it toward a speaker or monitor. This causes a feedback loop (sound goes out of the speaker into the mic, out of the speaker into the mic at the speed of sound, creating that familiar, painful squeal). INSTEAD, make sure the microphone is pointed away from all speakers.

- When shopping for a microphone, DO NOT simply settle for the cheapest option. INSTEAD, do some research, go to the store and try out several different models, learn what meets your needs, and then get the very

−Hilary Ann Feldman